BOOKS: |

| New Releases |

| Chicago Crime |

| Chicago History |

| Chicago Sports |

more... |

| Favorite Authors |

| Photographs |

A World of Books & AuthorsPersonal Observations on the Joys of Reading

|

Charles Dickens wrote Oliver Twist from this address on Doughty Street in London. Charles Dickens wrote Oliver Twist from this address on Doughty Street in London. |

I first became acquainted with Charles Dickens, through the Classics Illustrated edition of Oliver Twist, prompting me to the library where I found the beloved, but slightly dog-eared novel awaiting. Twist was my formal introduction to serious literature. During my first visit to London in June 2001, I toured the great master's last surviving residence at 48 Doughty Street. In this modest, four-story brick dwelling, located on a small, private road, Dickens penned twenty-two installments of the book that was to eventually become the classic Victorian novel for serialization in Bentley's Miscellany. The completed volume was published in book form in November 1837.

I discovered Theodore Dreiser's Sister Carrie in 1979, and became a devotee of the great urban realist not only because of Dreiser's extensive Chicago connections, but more importantly the power of his words captures the grim underpinnings and exploitive class differences of the Gaslight era. Even now, I often revisit the last 100 pages of this magnificent novel. The shame, the degradation, and the ultimate downfall of George Hurstwood are among the most evocative episodes in all of American literature.

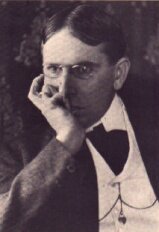

Theodore Dreiser, the brooding urban realist, and author of Sister Carrie. Theodore Dreiser, the brooding urban realist, and author of Sister Carrie. |

Theodore Dreiser is my literary "inspirer." When at the age of thirty, I set out to re-write Sister Carrie (I ridiculously titled it Sister Kathy) establishing it in the present day with the protagonist working a dreary sales job in a large Chicago department store not unlike the stone masonry fortress of Sears Roebuck and Company at Irving Park and Cicero Avenue where I toiled for 13 wretched and wasted years of my life. But after 200 pages of unmitigated drek I abandoned the project, only to find that another writer had the same idea in mind. Her novel was actually published in 1988, and I found one copy resting on the shelf of City Lights Book Store in San Francisco—but nowhere else.

I have read much of the Dreiser "canon" and heartily recommend An American Tragedy (arguably the author's most famous novel based on the 1906 Chester Gillette-Grace Brown murder case in upstate New York). So much of Dreiser's writing is introspective autobiography. The Genius is his much-maligned depiction of his early creative life (in novel form), but the blue-nosed censors banned it in certain Bible Belt locales for the sexual overtones. Mainstream critics (apart from his respectful disciple H.L. Mencken who considered it one of the greatest books ever written) were mostly unimpressed.

Newspaper Days, the second half of a lengthy two-part memoir injected with Dreiser's crusade against moralists and philistines, is a far superior and richly detailed account of Chicago, St. Louis, and other ports-of-call where Dreiser plied his trade as a struggling general assignment reporter in the 1890s before striking gold as a novelist. Newspaper Days was a pleasurable end-of-the-workday escape for me, as I settled comfortably into my seat on the Metra commuter rail line ferrying me home from my downtown office at Grubb & Ellis Company in the early winter months of 2003.

A Hoosier Holiday (the author's sentimental Indiana homecoming with incisive observations on American life) was published in 1914. Twelve Men (remembrances of the dominant male figures in life who shaped his outlook) followed. In old age, Dreiser visited Russia and was thoroughly duped by the false idealizations of the communist movement by his Russian hosts. Thus, he decided to align himself with the far left ideologues much to the great despair of the practical thinking members of the nation's literary community who wondered if he had gone mad.

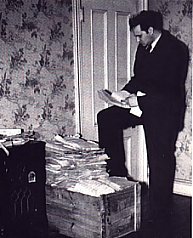

Thomas Wolfe, submitting his first draft Of Time and the River Thomas Wolfe, submitting his first draft Of Time and the River |

Thomas Wolfe wrote with uncommon fury because he was driven by the furies. Blessed be Charles Scribner's editor (extraordinaire) Maxwell Perkins, for recognizing the enormous talent of the gifted young North Carolinian, and bringing his weighty manuscripts to print. Wolfe delivered thousands of pages of his first draft of his autobiographical novel Look Homeward Angel and its sequel Of Time and the River, in a trunk to Scribner's Manhattan editorial offices. His tumultuous love affair with the much older theater maven Aline Bernstein (the character of Esther Jack) is told in two grand and stylish novels of New York City set in the early 1930s, You Can't Go Home Again and the posthumous sequel, The Web and the Rock. The latter volume was my personal introduction to Thomas Wolfe, and his soul-searching protagonist George Webber.

Every one of his sentences sweat emotion; the raw human condition sizzled to perfection by a magical wordsmith who compensates for occasional plot lapses with his superior command of the language. You Can't Go Home Again, part of his Webber saga, became a catch-phrase of mid-20th Century pop culture and its seems to be the one book that captured the hearts and minds of campus intellectuals ccoming of age during World War II. Wolfe is the author most cited by budding authors belonging to the "Norman Mailer Generation" of writers, a select group that also includes Irwin Shaw.

Harry Mark Petrakis is a captivating storyteller, and eloquent after-dinner speaker. Harry is the author of many famous books set in Chicago including Pericles on 31st Street, and Reflections: A Writer's Life, A Writer's Work, a memoir of the writing life and coming of age in Greek Town (the Delta) during the Great Depression.

To my astonishment, I learned that Harry is a lifelong friend of Dr. John P. Graven, former principal of Taft High School, my alma mater. I invited Harry to be our keynote speaker at the Year 2000 Society of Midland Authors Awards banquet and he did not disappoint. Harry recounts the mundane incidents of childhood in such a way that elevates his listening audience to high levels of anticipation, converging with inevitable tears and laughter. In July 2003, Harry send me a copy of his latest novel Twilight of the Ice, set against the backdrop of the rail yards of industrial Chicago in the 1950s; a time in our recent history when the Windy City still had an industrial base to speak of. Harry penned a message that is universal to all of us who write books because the printed word stirs our souls. He said most eloquently:

"I've written about eighteen times now and yet each time provides its own reassurance, the culmination of a journey that began with a vague conception and a blank sheet of paper. That journey to complete the book is as labored and as precarious as any voyage across some uncharted sea."

James T. Farrell must have been a fascinating world-class cynic, but I do not necessarily think I would have had the patience of mind to indulge his melancholia in a social setting. His inability to duplicate the success of his Studs Lonigan trilogy contributed to the bitterness he felt much later in life. I finished Studs in 1979, and saw so much of Dreiser in Farrell, that I began to wonder if it is the city that shapes the writer's outlook, or the brutalizing forces of Social Darwinism afoot in that same great city that drove the central characters of Carrie and Studs to despondency and an early grave. I cannot get past the opening pages of most of the Hemingway novels, but F. Scott Fitzgerald's seminal work, The Great Gatsby, appeals to my romantic notions of star-crossed lovers, Jazz-Age parties and Greek tragedies.

|

Dreiser both admired and envied Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951), the iconoclastic sage of Sauk Centre, (a.k.a. Gopher Prairie) Minnesota. His nomination for the Pulitzer Prize for such esteemed work as Main Street and the clever and sarcastic Babbitt, inspired jealous enmity within Dreiser and his legion of supporters, but Lewis' eventual award for Arrowsmith (although he turned it down) was deserved acclaim.

Babbitt happens to be my favorite Lewis novel, for I have observed and experienced much "Babbitry" on my own in my little corner of the world on Chicago's Northwest Side. I'm sure we all have at one time or another. The trick is to learn from it, but not necessarily condemn those that practice it because we are all guilty of the sin, if only occasionally, are we not? The "George Babbitts" of the world have seemed to have figured out this business of living and at least tried to make due with the cards they were dealt. Sheldon Norman Grebstein summed the author up best when he said that Lewis, "was the conscience of his generation and he could well serve as the conscience of our own."

Recently I have taken up John O'Hara, with a reading of Butterfield 8, Appointment in Samarra, and a collection of novellas published in 1960. Class divisions, modern tragedy, mistresses, madams and Depression-era hangers-on; country club dandies, and speakeasy drunks doomed by their own greed, dishonesty and envy are the underlying themes of this great social novelist's poignant writing;

John O'Hara, author of 14 great "sociological novels" of the twentieth century was obviously influenced by Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis in his descriptions of the minutiae, the status seekers and ragged class divisions of the town from whence he came. Alfred Kazin said his writing portrays the "American Establishment." But such modern day authors as Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Fran Lebowitz, and John Updike found John O'Hara, author of 14 great "sociological novels" of the twentieth century was obviously influenced by Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis in his descriptions of the minutiae, the status seekers and ragged class divisions of the town from whence he came. Alfred Kazin said his writing portrays the "American Establishment." But such modern day authors as Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Fran Lebowitz, and John Updike found |

"I want to record the way people talked and thought and felt, and do it with complete honesty and variety," - he observed in 1960, thus passing down the catechism of good writing to every aspiring author. O'Hara has often been compared to John Cheever and Raymond Carver, while others who are less generous in their praise dismiss his books as out-of-date and little more than grocery-store check-outline fare. Doubtless to say that there is no statue of O'Hara standing in the town square of Pottsville, PA, whose way of life he maligned through 14 novels and 402 short stories, but so desperately wanted to be a part of.

In the same tradition as O'Hara, but with stories spanning the close of World War II through the 1960s, comes Richard Yates, author of the superlative Revolutionary Road, which he began writing in 1955, the year Sloan Wilson published The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (yet another tale of characters bathed in the acid bath of rigid suburban conformity, but struggling to find a way out). Gray Flannel and Revolutionary Road are markedly similar; but Yates is a darker, more pungent brew to sip.

Maybe that is why Natalie Wood decided to scuttle plans for a movie version of Road, and in the process inflict immeasurable hurt and disappointment upon this poor, troubled man. His writing was shaped by a grim and brutal struggle to overcome alcoholism, a bi-polar disorder and a rapid descent down the slippery pole from fame to obscurity.

Yates, the impassioned political idealist was a man of blinding contradictions. He wrote speeches for Robert Kennedy; but lived in squalid Manhattan apartments and stored one of his manuscripts in the freezer. He died in 1992, and though nearly forgotten, he was widely acclaimed during the short time he occupied the public stage. His stories are full of black irony and unhappy endings. But then, life is never as simple, or as sweet and delightful as a chocolate shake or a stroll down through a wooded glen on a summer morn. Yates walked on the dark side long enough to understand and appreciate the bitter disappointments associated with the literary life.

I would have loved to spend a few hours in conversation with the late Herman Kogan, co-author of Lords of the Levee, one of the books that inspired my peculiar fascination with the sinfully wicked vice dens of old Chicago, and the political overseers who collected the nightly swag. Herman provided me with high praise when he endorsed Chicago Ragtime prior to publication in 1985, but I never had the opportunity to personally meet and thank this grandiloquent lion of Chicago journalism. Fortunately I have come to know his son, Rick Kogan, now a veteran Tribune writer, host of the "Sunday Papers" on WGN Radio, and author of Everybody Pays. In a tough, ego-driven business, Rick is a class act.

|

Here's what I remember best about Mike Royko, apart from my obligatory reading of Boss, during my freshman year at Northeastern. In 1993, I delivered the eulogy at Bill Reilly's wake in Evanston. Bill was a cantankerous old Irishman (half Jewish, or so he claimed), an ad-man, an idea man, and a champion drinking man who helped me kick-start the Merry Gangsters Literary Society into high gear with another dear old friend Nate Kaplan, who has since crossed the great divide. When Bill Reilly passed I notified Royko at the Tribune, recalling a great barroom story once told to me by Reilly.

It seems that several toughs were harassing Royko one night while trying to eat his cheeseburger in Billy Goat's Tavern. Reilly was sitting at the other end of the bar lost in a stupor, when he heard the commotion and spied Royko assuming a defensive posture as he prepared to take on the younger ruffians. Bill arose from his barstool, stood shoulder to shoulder with the newspaperman and said, "Now let's make this a fair fight, what do you say boys?" Needless to say the toughs hastily retreated, and the matter was forgotten for many years.

On the night of Reilly's wake, Royko slipped into the funeral parlor unannounced. I spotted him standing in the rear of the room, and he looked at me and nodded. It was my queue to bring him up. Royko spoke for less than two minutes, thanked Reilly for bailing him out of a tough spot and exited the building. Nothing more needed to be said.

If you begin to sense that I am a man who appreciates and values the work of earlier generations of authors (particularly from the school of realism) as opposed to the writers of contemporary "minimalist" fiction, you would be correct. But then, I have often been accused of dwelling in the past rather than looking to the present or future with any degree of sustained optimism. That much I suppose is true.